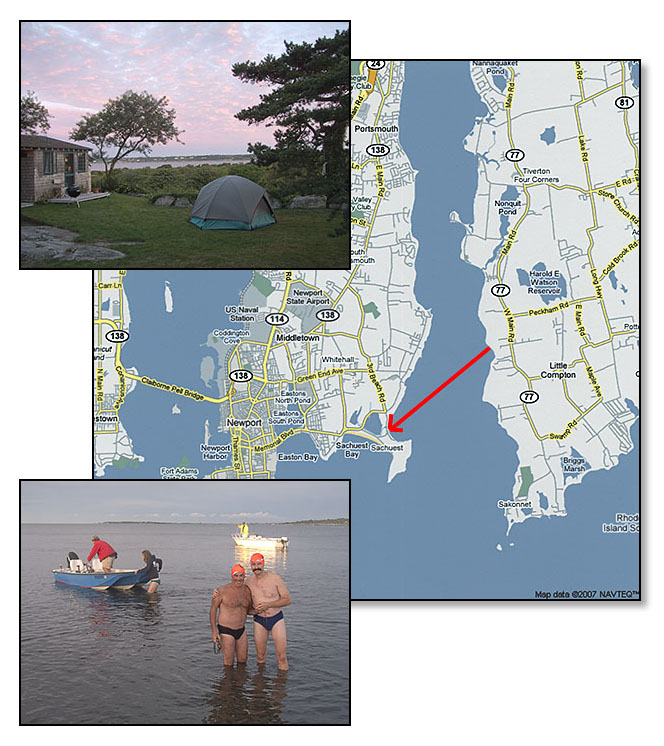

OPEN WATER SWIMS / JOHN FORASTE & FRIENDS

2007: Crossing the Sakonnet River / Little Compton to Sachuest's 3rd Beach

|

Date: 21 August 2007. Distance: 2.87 miles (4.6 kilometers) (calculated on mapmyrun.com). Route: Across the lower Sakonnet River: Brown's Point in Little Compton to 3rd Beach in Middletown. Water Temperature: 65.5º F (temperature during swim at Newport Station per NOAA website). Air Temperature: 55-57º F. Time: 1:32. Swimmers: Phil Weinstein & John Forasté. Boaters: Charlie & Sophie Whitin and Preston Granbery. Photographs of our tent at Stonepile and entering the water (Swimmers: Phil & John. Boaters: Charlie, Sophie & Preston). Photographs by Diane Forasté. The Swim by John Forasté My wife Diane, our dog Sage, and I stayed in our 2 person LL Bean tent the night before the swim on Charlie, Sally & Sophie Whitin's beautiful piece of land overlooking the lower Sakonnet River in Little Compton, Rhode Island. They call the place that has been in Charlie's family for years, Stonepile. Their cottage is built on land that was first leveled out by piling stones - many more like boulders - that are plentiful there and form miles of magnificent stone walls throughout Little Compton. The air was cool, but lovely - and still. Phil Weinstein and I regularly workout together and have done other open water swims. The plan was for him to drive from nearby Westport to meet us at Stonepile and walk the 10-15 minutes down to the water. Meanwhile, Charlie and Sophie, his delightful 16 year old daughter, would tow their Boston Whaler to the water, launch it and meet us at the starting point for a 6:00am start at sunrise. Early is better when the water is usually quieter and before the wind kicks in. Charlie had freshly mowed the trail through the high Rhode Island brambles and wildflowers. The walk in the pre-sunrise light with Diane, Phil and Sage (happily darting about like a puppy far younger than his 8 years) was like walking through a bit of paradise. Charlie had also invited his neighbor, Preston, to join us with his boat. But he seemed doubtful after hearing about the 6:00 start. To our pleasant surprise, he was not only there, but the first one at the starting point. On the beach, looking across to the sliver of land that was 3rd beach, our destination, Phil asked why we weren't swimming to the less distant houses just to the north. I smiled. The air was quiet and beautiful. My chamois shirt felt perfect, warm and cozy in the mid 50º air, down 10º from 64º at midnight. Entering the water with only a Speedo swimsuit, goggles and swim cap (actually a double layer of 2 caps) is not something you would normally choose to do on such a morning. (We consciously decided not to use wetsuits - it was part of the challenge.) Actually, I think Sage - wanting to come too - was the first in the water just before 6:30. The first few minutes in the water felt a bit chilly but ok, similar to upper Narragansett Bay off Barrington where I've been working out lately. Otherwise, the water conditions were wonderful. We were off. Shortly into the swim, however, I realized I wasn't kicking the chill. I asked Phil how he felt. He was fine. As we continued, I told myself that it would pass - but it increased a bit. Our intent was to swim together and I was reluctant to suggest anything else. But the chill persisted. Was it meant to be that we had the 2 boats? I asked Phil again how he felt. He was perfectly fine. I told him I felt the need to push harder in order to generate more body heat and asked if he would mind staying with one of the boats while I went with the other. He was totally agreeable. So, Charlie & Sophie guided me as Preston continued on with Phil. This was a good decision. I began to feel better - still chilled, but less so and nothing serious. I was able to lengthen my stroke, get into a good strong rhythm and take in the wonderful open sky inhabited from my vantage point by Charlie, Sophie and their boat. They seemed to be enjoying themselves. Since I breathe left every stroke, I could see Charlie pointing this way and that to Sophie. Swimming at 1.9 mph (the speed we calculated after the swim) gave him plenty of time to guide not only me towards 3rd beach, but Sophie about the waters he grew up on. In fact, Charlie's father made a similar swim while in his late 50s with Charlie and his wife Sally rowing in nothing more than a tiny dinghy. During previous open water swims, I had been accompanied by kayak(s). This was the first time with a boat under motor. I mentioned to Charlie that I was a little concerned about the fumes. We decided that, if they became a problem, we would try repositioning the boat(s) relative to Phil and me. During the swim, I smelled the fumes only once, and that only briefly. It was only after the swim that I learned this was not the case for Charlie and Sophie. Traveling at under 2 mph, but with a soft breeze behind them, they found themselves sitting in the fumes for the entire crossing. I had been clueless and felt terrible for them. But this neither caused Charlie to complain nor deter him from maintaining a straight course - clearly helped by years of sailing and his coxswain skills developed during his rowing days at Princeton. I made land fall in 1:32, just after 8:00am. While I felt good throughout - except for the chill - I was surprised by the time. In truth, it felt more like 2 hours. Phil, wrapped in a towel and a big smile, pulled alongside in Preston's boat as I approached the beach. He had a good swim to the area he had originally proposed and I made it to 3rd beach. Everyone was pleased on this beautiful late summer morning. Phil's plan was always to go one way. My hope was to make it round trip. It was now time to turn back. Should I? The water and air were still chilly and I had some irritation where my arms had rubbed against my body on every stroke (I had forgotten to put vaseline on to prevent this). And Charlie gave a report on the wind. It wasn't bad, but had clearly picked up, creating a slight chop - and would be heading right into us. Standing in the cool air in waist deep water after swimming almost 3 miles is not the time to make such a decision. I hopped into the boat and pulled on some warm clothes. I should have at least tried the return. The Swim by Charlie Whitin (This is the same swim, but as told by Charlie) " ... The simple act of a [swimmer's] stroke put diamonds in the sea." [-- apologies to Donovan P. Letch] The First Annual Brown Point or, how about the 'What's the Point' Swim across the Sakonnet? It takes thirty minutes to drive to Third Beach without any traffic, and only three times that to swim there. In a Whaler, it takes about six or seven minutes, shore to shore, at most ten. What I want to say is that in no way do I minimize the effort or the open water swim. It is an impressive feat, something I would not dare do, and something that I most likely could not do, even under duress. There is no stripe to follow as in a chlorinated pool. Water temperature at 68 degrees. Put yourself in their Speedos: now, would you try to do this? And that, in the shell of a nut, is why I think these swimmers through distant waters are vaguely, shall I say it, heroic. Who, what, where, when, and why? I eat breakfast with these guys on Tuesdays at Louie's, whichever, whatever. The group breakfasts together after their morning swim in the Brown U pool which was fine and a raison d'etre for years, that is until the pool was closed this winter for structural reasons, causing a diaspora that has often reduced the group to one swimmer and two friends. I am the last friend, a friend of a friend, and when thoughts turned to summer and previous open water swims, I was the one who volunteered a beach and an escort, somewhat struck by the novelty. My friend and their previous escort wanted a reprieve from kayak duty. Thinking like the lawyer I am not, but as a moderately experienced sailor, I noted that a kayak was inadequate as a rescue device. Fortunately, it had been utilized as a direction finder for the swimmers and nothing more. I said I could muster up a larger, motor powered craft which would prove safer, even then, I suppose, to provide a false security, and a launching place in front of our house. And things were set in motion. Along with my imagination. Of course the mental wheels kicked into gear and the swim in my mind evolved into epic proportions, with two, then four, then six and ten and more. Including a flotilla, no, a veritable armada of pleasure craft, pennants flying, like Prince Philip's launch at the Henley Royal Regatta, "The Windrush" following the crews. Or so it was in my dreams. Think about it. Up at five to swim on a chill day at six, across a seemingly tranquil channel with all manner of marine warfare going on beneath the surface, a channel that widens out into Rhode Island Sound, part of the greater Atlantic Ocean. A channel that is deep, full of fish and dark, impenetrable mystery with unexploded depth charges, a U-boat sighting by my grandfather in WWII and schools of fiercely fighting bluefish ripping the life out of menhaden. The reality? Simple. The two breakfasters from Louie's were to make the swim. Our friend and sometime masters swimmer from California trained somewhat for several months but arrived in awe of the unknown fellow swimmers and thoroughly daunted by the water temperature. The coup de grace came when we informed her that the start time was six a.m. There was a famous baking duo from Providence who had to work, alas, and could not come. And the all star swimming coach from Philadelphia had to deliver a child to her college orientation in Maine, and yet another swimmer friend of friend simply never materialized. And so as the chips fell, the breakfast regulars appeared at the designated hour, exactly two. Their friend and mine, traumatized by his concern for the well being of his wards did not want to know anything at all, no details, much to his relief. I need to digress for a moment. My sense was that it would be a challenge in the end to find a motor escort at the final hour. There were several nods, months in advance, but I had my doubts they would materialize at the dawning hour. And then this amazing thing happened. It happened that a small blue whaler sat on the road side with a "For Sale" sign on it. I had stopped and said it looked nice to my wife, perhaps more wistfully than I realized. I had called to see how much and then, characteristically, sat deliberating, not wanting to spend the money, secretly hoping someone would buy it and put me out of my misery. But no: this was not its destiny. As it turned out, my wife had mentioned this to my sister, presently visiting from Switzerland. And at the cocktail hour, while seated in the living room around the 4th of July, I looked up to see the very same boat rolling down into my cousins' driveway next door. "Damn," said I. "Jeff bought it - It must have been a good boat!" And suddenly, the pickup towing it reversed and drove into our driveway, and my sister, laughing, said "It's yours!" And so it came to pass that I acquired my first motor boat at 58, but no matter: it made me feel like I was ten. And that's enough sidetracking. Back to the swim. When I was a boy about six years old, my uncle Charles Thaddeaus hung me over the transom of a bass boat near the Sakonnet Lighthouse. It was one of the classic wooden lapstrake or clinker-built hulls, inboard engine variety, with a windshield and a cuddy cabin, the sort called a "Bass Boat" that are so prized today. There are only a few left in the harbor nowadays and they catch every fisherman's eye. I remember screaming, absolutely terrified, while he held me by the ankle, my head a yard above the infinitely deep blue ocean, he laughing while his wife Helen and sister Edith told him to "put him down" which he eventually did. Nor does it help quell my experiential and instinctual fears that I had just watched a solid week of "The Discovery Channel's" "Shark Week" on television, transfixed and horrified as it resurrected memories from the time when I would go out with the fishermen when they pulled the Sakonnet Point Traps. Sharks, large ones, were caught often in the nets. I thought maybe they were not really the "pelagic blue sharks" that I remembered; however, one of the fishermen told me that they do occasionally pull large blue sharks, even today, fifty years later, so my imagination did not get the better of memory, at least not this time. Blue sharks are white on the bottom and blue on top for ocean camouflage. They are opportunistic predators and nothing that I would ever swim among by choice! How could it be any surprise that I harbor fear that something huge and horrible will come up out of the depths and take large bites out of me? I can never forget what I have seen and heard. I have read the graphic description of the sinking of the Indianapolis, In Harm's Way by Doug Stanton and I have watched Spielberg's movie "Jaws" which vies with Hitchcock's "Psycho" as nearly everyone's 'scariest all-time' movie. All the same, I play the odds every time I jump into the sea, knowing that such an encounter will never occur, but I am thinking like the hapless Jim Carey in "Dumb and Dumber," and that even at "one in a million" there is still a chance! To make things worse statistically, the swimmers plan to leave at daybreak near the mouth of the estuary, and I have just learned how both of these decisions increase their risk substantially. The merging of warm and colder waters, the mix of many species of baitfish attract more and bigger fish. Swimmers in the ocean need to seek out the smoothest water conditions possible. They must avoid dangerous boat traffic and wind. I am afraid that sharks do not distinguish between weekends and weekdays, though we did, if only to avoid other boats, and big fish eat smaller fish. That's how it all works. Planned in advance, I had time to imagine many scenarios and to pursue all sorts of tangents, some ordinary and a few bizarre. Quick to mind came Burt Lancaster in the movie made from John Cheever's story "The Swimmer." Lancaster had it relatively easy, though his odds were stacked heavily against him. For him, the "sharks" were most likely to be the sexually predatory females and latently gay men that he intersected with as he crawls and drinks himself across Scarborough-on-the-Hudson, and the lemon-twisted shark within if I am allowed to twist things, shaken not stirred. My father swam his way across once in the early 1980s at close to sixty years in age. It was a sultry day and he was swimming while my then girlfriend and I paddled a cheap plastic rowboat along side. I sensed what he was up to, even though he had never said a word. Eventually one of us spoke. "Might just as well keep going as return; we're more than halfway there." It was kind of now-or-never type of decision, a seize-the-moment or lose it, and he kept on swimming further out until crossing became just as easy as going home, except he did not realize he would be fighting the current towards the end and we had to compensate his course for him, or he might not have ever made it. His lips were blue as Barack Obama's towards the end, which was not good. And he swam a wide "S" shaped course, slapping at the water, covering at least an extra third of the 2.4 mile distance across. The whole thing was so unanticipated that we had nothing warm for him to wear once he made it across, without water or food. We in our bathing suits. We forced him to row us home to keep from being chilled. It all ended well. My mother's much older sister, Aunt Janie, told us all how Dad was a "crazy fool" which was great because she was neither. She was kind of conservative, thinking back, and maybe something of a grump, too. We were proud and amazed by the sheer bullishness of his act, a testimonial to his endurance and tenacity as well as to the sentiment that nothing that is worth a darn comes easily. We knew no one else who had done this or tried to do such a thing at the time. We did know of one neighbor who swam out into the river, but his intentions were suicidal. His body had washed back upon the shore. We never knew any more details; it was an unsubstantiated rumor. Dad's motives were just the opposite: he just wanted to see if he could do it, like the bear climbing over the mountain, to see what he could see. Dad wanted to survive; it was an Outward Bound sort of thing. Early on in the summer, I started to watch and evaluate every morning for its 'swimability.' In June, most of the mornings were not good; by July the ratio had improved, and in August, many of them turned out fine. Still, there were a few bad ones and I worried about having to tell the swimmers "no, not today." My wife worried about our personal liability, wanting them to depart a mile south from Taylor's Lane instead of from our beach for this reason. Only a few days before the planned date, my journal entry reads: August 17th. Early this morning would not have been ideal for the swimmers. It was very fogged in and they would not have had an easy target to swim towards, nor would I have had something reliable to look at. As it turned out, the fog lifted and all would have been just fine. But how would we have known? Nothing is for sure. I watched the early morning conditions to see what it would be like at six. Dark at five, dark at five-thirty and first light only ten or twenty minutes before the proposed swim time. No wind most mornings giving way to a brisk onshore breeze from the southwest by midday. Equally important, the ebbing tide would slacken about the time the swimmers were to reach the Third Beach side, and it would boost them along on the return trip across the estuary. It became apparent that the swimmers were not 'boat' people, they were athletes, and they were relying on me to drift along beside them. They did not fathom the depth and degree of my readiness to guide and, if need be, my ability to save them. They have no idea how difficult it is to pull an unconscious person out of the water without a davit or a pulley. August 20th. I prepped the boat for tomorrow morning's swim. The little pin - a sort of one way check valve - in the gas line fell out. I had no choice but to drive all the effing way to Seekonk only minutes before closing time in order to find a last minute replacement. Frustrating and tiring, but it would have been much worse had I not noticed it until six o'clock in the morning and we would have had no choice but to postpone the swim. John and Diane are here, sleeping in their tent with their three-legged dog, Sage. Our nasty old dachshund bitch has been less than accommodating. We are going to be up early tomorrow morning at five. Sophie and I will launch the whaler in Tiverton and meet everybody in front of the camp. Only John and Phil are planning to swim. Sally, Diane and Jan are planning to stay at home, sleeping in and they will watch the event as it unfolds from the telescope on the porch. Wish all of us luck in our endeavors tomorrow. To bed. Amen. In the evening, John consumed the ritual meal of spaghetti and beer, known by endurance athletes as carbohydrate loading. He and Diane slept by choice in our backyard in their tent, serenaded by a choral from several dozen coyotes. We had beds: they preferred the great outdoors, and who could put a knock on that?! And a final journal note before the swim: August 21st. Up in the dark: why are we doing this? The relief upon rising is the tranquility of the morning. No wind, no waves. Yes, it is cool, but as good as anyone could have hoped for. I woke Sophie, who does not want to get up at all, at first. I go outside and awaken John and Diane still fast asleep in their tent in the kitchen yard. Sage barks once, startled by my voice. And suddenly there is the commotion of people up before the dawn with a mission, paths crossing between bed, bath and breakfast. Sophie and I will launch the Whaler. John and Diane will walk the path to the beach and Phil, the wild card, will drive here at any moment and walk to the beach with them. Sally and Cosi are curled up in their warm bed. And Jan, I joked, was hiding under her pillows and blankets pretending not to hear a thing. She felt unprepared to do the swim, somehow evading John's persistence. He could not lure our Californian visitor into the Sakonnet's chill waters, even offering her a full body wetsuit, but to no avail. Morning dawned on the destined day, with the sun coming up in what I call reverse fashion, its first light reflecting back from the Newport side - angling from the west - instead of directly from the east, where the slope obscures it for a little while. I have always loved this unique aspect of living on the Sakonnet in Little Compton. We all slept early and the five o'oclock awakening hour arrived all too fast for most of us. Once the cobwebs were out of my eyes and Sophie's, we were quick and focused, and it was fast becoming a 'great-to-be-alive' kind of morning, with the unfamiliarity and excitement that makes you think you ought to do this sort of thing more often, at least until the reality of actually doing it sets in. Do this often enough, after all, and sleeping-in might become a novelty. The great news was that there was no wind and there were no waves. Conditions - more perfect than we could reasonably have hoped for. Sophie and I left the house early, before Phil Weinstein arrived. He was not reachable by phone, and we left wondering if he would appear at all. And then there are these recollections taken in proper, Wordsworthian tranquility, after the water's been toweled off and the chill is gone. The launch at the Fogland boat ramp went without a hitch, or actually, with a hitch to tow the trailer. My concern: I have yet to register the hitch and fear - you must understand by now that I am the worrying sort of person, engaged in discovering what might go wrong before it actually does - that a trooper will notice this and give me a ticket. In the water in minutes, we pushed the throttle forward and flattened the Whaler out on a plane, speeding up to Brown Point at 30-something mph, accompanied by the first morning's blinding sun and a cool offshore breeze, noting the conditions were absolutely perfect! Around the point three dark silhouettes stood shadowed on our stretch of the rocky shore, along with to our great surprise and pleasure, our friend Preston Granbery in his boat, lurking like a pirate by Uncle Joe's breakwater. This was fantastic good fortune, as it meant there would be some kind of back-up in the event our engine failed or anything else went wrong, and a measure of instant relief for me, not altogether confident of my newly purchased, but already well-used craft and engine. Diane and Sage were present for the "Bon voyage!" and without much delay, their game faces on, John and Phil in their speedos, donned fluorescent orange "Save the Bay" caps and goggles, and at 6:29 they took the plunge, beginning the 2.9 mile swim to Sachuest, now in full sun, while we were still shadowed. Mercifully, no one commented on the name of the boat: SWEEET ASS, which is actually not its permanent name, but a temporary moniker with the remains from scraping most of the word 'MELISSA' off, then realizing in an enlightened moment that the 'A' at the end could be placed where the 'I' had been before, if you follow. I am sure it amuses me more than anyone else, and it might truly offend a few of the politically inclined. Probably no one noticed the name at all. Edit that. Only the night before, we had discussed the best place for me in the boat to lead the swimmers. They both breathed to their left on every third stroke and all they would need to do is stay parallel with me. In this way they would never need to crane their necks to look forward. I gave them a virtually straight course across. Trusting me, they would never have to think, just concentrate on finding their rhythm and swim, while I compensated for any drift caused by current or the wind. There is no way for them to know how competent I am at this, or that I have been doing this as a coxswain and a sailor for most of my life. The lowest idle on the Mercury outboard was still too fast for the swimmers, so there would be a constant shifting from neutral into the slowest forward. Unfortunately for Sophie and myself, the following breeze was more or less exactly behind us at more or less the same speed, meaning that we would travel in a noxious cloud of monoxide of our own making the entire way across the river. The good news was that John told us early on that he could not detect any engine odor at all. Initially this had been a concern of ours, and especially among John's, who is as concerned with energy in swimming as he is about fuel. In the past, kayaks had accompanied the swimmers and this was never an issue. John drives a hybrid car; he and Diane will build an environmentally accommodating house on Bundoran Farm in Virginia a few years hence. It must have been close to halfway across that John and Phil decided to swim separately. John had periodically slowed down to breaststroke in order to let Phil catch up and he said that he was getting chilled. So quickly, Sophie and I, already in the lead, determined to stay with John, while Preston stayed back with Phil. As we continued, the courses of the two swimmers diverged quite rapidly, which alarmed me at first, watching as Phil and Preston appeared to stray off the course and head directly for the nearest Middletown shore. We watched them veer, soon many hundreds of yards distant. Seeing Phil's cap as occasional flash of orange, and then only a random splash from his crawl. A small dragger trawled very close to him. I worried that Preston was following his swimmer and not the other way around. South of us, Sophie and I watched a modest sized school of feeding bluefish thrash on the surface, with terns and gulls of many descriptions diving on the baitfish that were driven up by voracious blues, perhaps stripers,too! The school was only 300 yards away, and we were a bit apprehensive about its getting closer, keeping a weather eye on the fish, to mix my metaphors. I have always thought a school of frenzied bluefish would bite anything in the water with them, but who knows, and more important, I did not want to find out, not here, not now. I see no difference between their feeding than, say, a school of piranhas in the Amazon. We continued onwards, pretty soon the houses and stairs down the Middletown rocks off of Indian Avenue began to come into sharper focus, and the shore we had left behind receded into shadow. John had made excellent progress and stayed precisely on course. For the final half mile, we nearly paralleled the Middletown shore, and at 8:01, John reached Sachuest's Third Beach, standing waist deep off of the beach. He had been in the water for one hour and thirty-two minutes. As he stood in waist deep water, devouring a banana, we did not encourage him to make the return trip, noticing how the wind had come up and that it would be blowing directly into him at about 10 knots. The return would be considerably more difficult, and the next thing, he was climbing over the side and into the Whaler, today's swim over, primary goal accomplished. Perhaps we ought to have been more encouraging? We motored back into a slight chop, the whaler slamming into the waves, the air freshening on our reciprocal course home. As for ourselves, Sophie and I were relieved to be heading back as the prospect of another hour and a half of in and out of gear was not altogether appealing, truth be told. Phil and Preston returned in one boat, John, Sophie and I returned in our boat. There the Returning Heroes were met at the beach, modern day warriors less than a mile to the north of the place where Benjamin Church and the Sakonnet Sachem Awashonks once buried their hatchet at the close of King Philip's War. We would reconvene at the Commons' Lunch for a Breakfast of Champions. Later Still: August 22nd ... And onto other things. I felt terrible yesterday from inhaling so much carbon monoxide from the outboard engine. With a slight following breeze, I had to engage and disengage the engine to not get too far ahead of John in the water, swimming parallel to us in the boat. As a result, the fumes just sat around us in the boat, stinking. At first I thought maybe I was simply tired from doing so many things the several days before and from getting up so early each day, but it wasn't only that. I ran to Windmill Hill and back to try and wake myself up before the party and this did some good, clearing my head somewhat. Spaulding [Gray] would have been so pleased to see me on the hill he writes of in the beginning of his book Impossible Vacation. Even Later Still: OK. I need to work on my story about the two heroes, Phil and John ... First line: "Besides my own father who swam the Sakonnet back in 1980 at the age of 57, I do not know any other swimmers who have pursued the challenge of swimming the three mile passage from Little Compton to Middletown aside from John and Phil. I know there must have been others, but I just don't know them. All went well yesterday, so well it almost seems routine. I wish to note that from my position in the boat or presently seated in this chair before this laptop: John and Phil were very courageous, no matter how many times or by whoever has done this before. Today, a moderate school of blues came within three or four hundred yards of the swimmers. We watched it carefully, concerned least it come much closer. I think about the pelagic blue sharks sometimes pulled from the fish traps off Sakonnet Point, lurking below, invisible to any surface swimmer. I thought about the varieties of fish, the currents, the ocean swell so gentle on this day that could in a matter of hours turn from tranquil to a maelstrom, from friend to overwhelming foe within a few hours. This very same beach was where my mother found a drowned sailor after the never named hurricane of 1938, walking with her father to inspect the aftermath of the storm, never forgetting the story and the image of a Portuguese fisherman clinging to a piece of thwart from one of the gondola's, rigor mortis locking his bruised white knuckles around the wood in a death grip. Who could possibly save himself in such a storm anyway by swimming, or not knowing how to swim? Many of the fishermen, unbelievably, did not know how to swim a stroke. This is the beach I personally never strayed more than fifty yards away from, let alone three miles. It is 'a breeze' to cross by sail or motor in fair weather, but actually in the water? In the heat-sucking, dehydrating 68 degrees cold salt water? I run on the roads, though not as I once could. There were the years when I would go off for ten and fifteen miles at a time, logging in a hundred mile week or the time I ran from Easthampton down to Montauk just for the challenge of it, with no plan for how I would return. Had I wanted to stop, terra firma lay beneath my feet. August 23rd: John wants me to write something about the swim. Good. This will make me do it, otherwise I will drift like my father, slapping at the water, going sideways as much as forward. August 25th: John now wants to swim from Land's End in Newport across the open water to Sakonnet Point, with me alongside. It is over six miles and I woke up worrying about it. My middle of the night feeling came on strongly. This is not something I want to tackle on my own in a 13 foot whaler, John in the water for nearly four hours. There are too many what ifs, I have too many fears. I just went through this; I don't want to do it again right away. I think this is not something I should involve myself in right now. The whaler is inadequate and not prepared or reliable. I cannot help John if there is any trouble. I hear the joyful noise of crickets and cicadas in the night. It is dark, there is a breeze rustling the tulip tree and the dampness drips from its leaves, the porch light shines on the wet lawn. My fears make me restive, they will not allow me to sleep. Not about another swim, but of many things, this being a very small one. A faint, distant surf crashes onto the tumbling rocks down at the shore as they have for always. It is such a pleasure, being awake in the middle of such a summer's night while those around me sleep deeply. I resolve to tell John no, this time. Swimming from Land's End is a risky concept, and not a good time for me to do this. Relieved with this decision, I relax, now feeling tired enough and ready to join the rest in sleep. Map data ©2006 NAVTEQ from maps.google.com |